The filmmakers of a recent documentary have been publicly called unethical, despicable, and completely lacking in journalistic integrity for their editing decisions. But can they also be held civilly and financially liable in a court of law for those same editing choices?

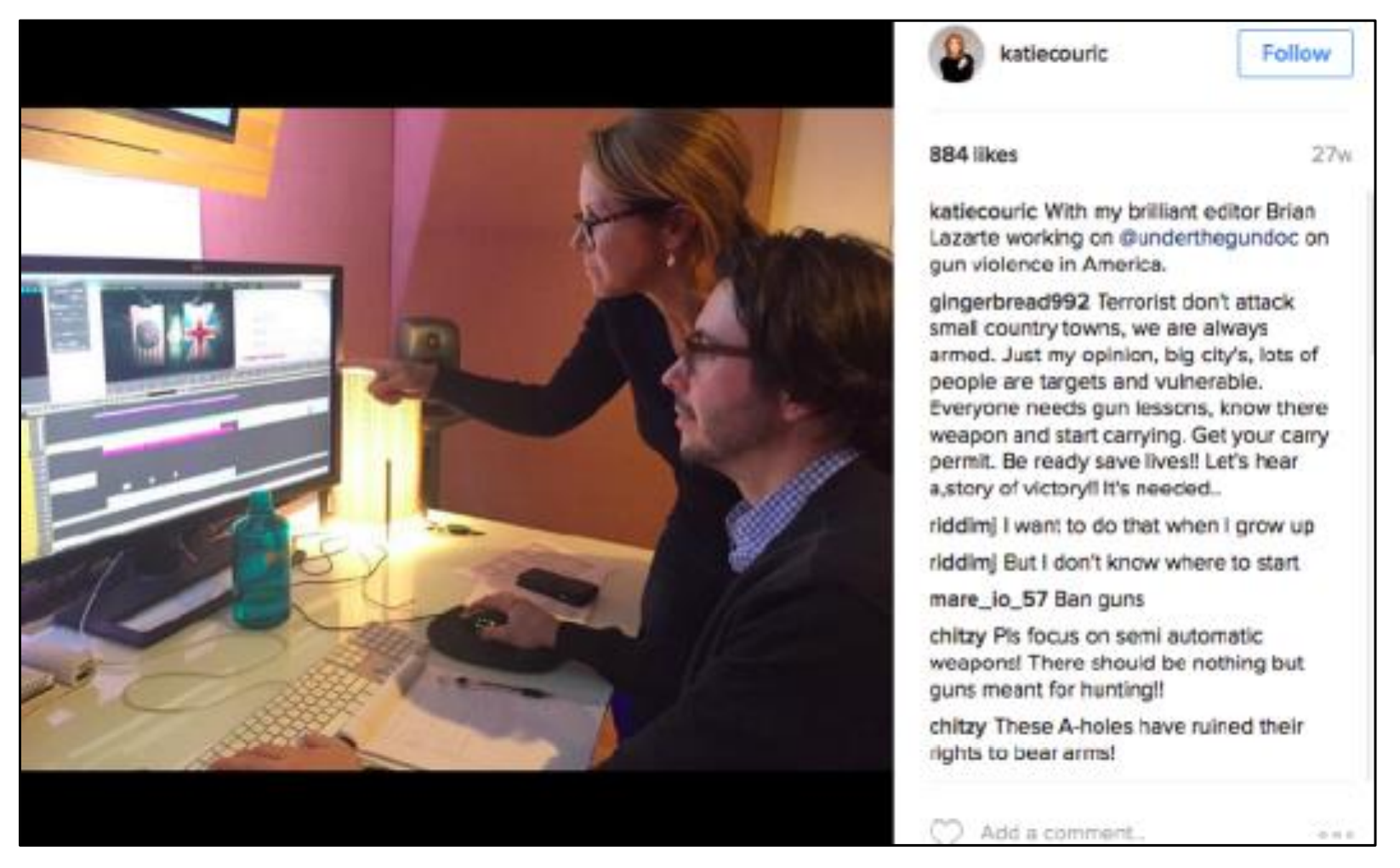

Katie Couric, documentary director Stephanie Soechtig, Atlas Film LLC and the film’s distributor Epix were named defendants in a lawsuit filed by the Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL), a gun rights activist group, and two of its members, licensed firearms dealer Patricia Webb and Daniel Hawes, a firearms and personal defense litigator (the “Plaintiffs”). According to the complaint, the Plaintiffs claim that the filmmakers interviewed them for the 2016 documentary Under the Gun, and then selectively edited raw footage to portray plaintiffs in a false light, creating a depiction that was recklessly false. The Plaintiffs are seeking $12,000,000.00 for compensatory damages, $350,000.00 per Plaintiff for punitive damages, plus costs and attorney’s fees for the Defendant’s allegedly defamatory editing choices.

The part of the documentary at issue involves an in-person interview with Katie Couric, where members of the gun rights activist group Virginia Citizens Defense League (the Plaintiffs) are asked about their views and positions on firearms background checks. Before the interview began, Couric and a cameraman asked the Plaintiffs to sit silently for 10 seconds while their “recording equipment was calibrated.” The interview began, and at one point Couric asks the plaintiffs “If there are no background checks for gun purchasers, how do you prevent felons or terrorists from purchasing a gun?” The Plaintiffs then provided a substantive, six-minute response explaining their views on the question. However, during editing, the Plaintiff’s responses were cut from the film, and instead of their responses, the 10 second pre-interview silent pause was added in its place, giving the appearance that the Plaintiffs sat there silently, dumbfounded, instead of answering the question.

“The film was edited to portray the activists as speechless and apparently unable to answer the question for about eight or nine seconds, despite them actually giving an immediate, six-minute long substantive answer.”

The complaint alleges that audio tapes made separately by the Plaintiffs prove that the activists had provided an immediate, substantive six-minute response to Couric’s question, and the filmmakers purposely decided to edit the film to make it appear as though they were “stumped”, and lacked the knowledge to come up with a response to support their stance on this key issue of public policy. They claim that this purposeful, intentional act in the editing room constitutes defamation, and their editing choice constituted a purposeful, malicious act with a complete disregard for the Plaintiffs’ rights.

The Law on Defamation

Defamation lawsuits against filmmakers are extremely difficult to win. This documentary, like all documentary films, is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, as it is considered free speech. In 1948, the Supreme Court in Winters v. New York, ruled that entertainment and news are fully protected by the First Amendment because “[t]he line between the informing and the entertaining is too elusive for the protection of that basic right [of a free press]. Everyone is familiar with instances or propaganda through fiction.” And in 1952, in the landmark case Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the Supreme Court ruled for the first time that motion pictures are a constitutionally protected form of expression. This means filmmakers are free to tell their version of the story as they see fit, with rare exceptions. But there ARE exceptions. Just like shouting “fire!” in a crowded movie theater, freedom of speech does not protect against certain harms like defamation or fraud.

So how does a filmmaker or editor ensure that they don’t cross the invisible line and open up the production to these types of civil liability issues? Know who you are filming, and have them sign a release.

Are You Interviewing a Public Figure or a Limited-Purpose Public Figure?

Public figures are held to less-stringent standards when defamation, fraud, and right of privacy claims are involved. In order for a public figure to succeed with a defamation claim, they are required to prove the defendant acted with “actual malice,” that is, knowing that the material was false or with reckless disregard for the truth. This is an incredibly difficult standard to meet.

It’s important to keep in mind that there are several different types of public figures. We’re all familiar with celebrities. But if you’re a filmmaker making a documentary about a newsworthy issue of public concern, you may find yourself interviewing “limited-purpose public figures”, that is, someone who is not a typical celebrity, but may be well-known with regards to a particular issue. This would typically be someone who volunteers as an expert in their field who hold themselves out to the public as an expert, or someone who has a unique perspective or experience about a particular issue. In the case of the Under the Gun documentary, the Defendants will no doubt claim that the Plaintiffs were limited-purpose public figures who volunteered to be interviewed as “gun experts” for a documentary about a newsworthy topic, and hence the higher standard of actual malice should be applied to them in order to establish their defamation claims.

But in reality, we probably won’t even make it to those delicious bits of legal analysis, as I can’t imagine the Defendants NOT having a fully-executed release on hand, signed just prior to the interview in question, that releases the Defendant-filmmakers from any and all claims like the ones at issue here.

What Does Your Release Say? Can a Someone “Sign Away” Their Rights to Defamation or Fraud Claims?

Filmmakers typically have a release signed by every subject they film, giving the filmmaker all-encompassing rights to use the footage how they see fit, including unflattering or misleading editing. Typical legalese in the relevant release clause would state something to the effect of, “I expressly release you, and your agents, employees and representatives, from any and all claims which I have or may have, including without limitation, invasion of privacy, right of publicity, defamation or any other cause of action, arising out of the production, duplication, broadcast, exhibition or other exploitation of my performance.” I can’t imagine the Defendants in this case NOT asking every single one of the on-camera Plaintiffs to sign an all-encompassing release, waiving their rights to any and all claims in the process. The complaint is silent on the issue of a release, however, so we have yet to see how this will come into play for the Under the Gun lawsuit.

Can You Be “Tricked” Into How the Footage Will Be Used?

Remember Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Borat” lawsuit several years ago, when the filmmakers were sued for defamation and fraud for making a bunch of college kids look like idiots on camera? The Plaintiffs there admitted they did sign a release, but it was only to appear in a foreign news program, not an internationally-released major motion picture, and as such, they argued, the release should be considered void. The federal judge there ruled in favor of the filmmakers, explaining that the broad language of their release enabled the filmmakers to do as they wished with the plaintiffs’ names and likenesses, regardless of any deception in the type of programming the footage was to be used in.

This is just one of the many reasons I insist on all of my filmmaker clients having up-to-date releases on hand at all times. An improperly worded release, or no release at all could have a severe financial and detrimental impact on your production company, and even you personally depending on the situation.

An Artfully-Crafted Release Will Avoid Most Issues, But You Cannot Contract Away All Types of Liability

Let’s face it. If someone wants to sue you, they will. Even if you have an air-tight defense, you’ll still have to pay money to defend yourself (but you should be able to recoup your attorney’s fees and expenses if your release is worded correctly). But there are some instances, that even with a signed, artful release on file, you still might find yourself in legal trouble. For example, no amount of legal language is going to protect a filmmaker, producer or a network if gross negligence is easy to prove in a particular situation. And there are many claims the signee can make to attempt to declare the release itself void.

As for the Under the Gun lawsuit, it would be interesting to see the Second Amendment do battle with the First Amendment, but my guess is this case will slink off into the night once a properly-signed release presents itself from the defense.

Just wanted to say thank you for this article, really saved me for a school project lol